zu der Buchpräsentation:

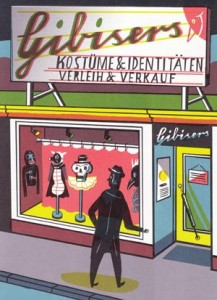

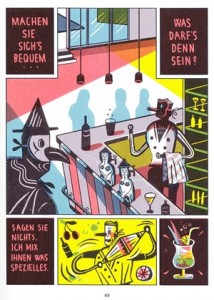

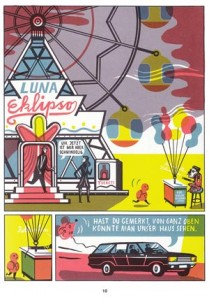

Artur Schnitzler “Traumnovelle” – eine Graphic Novel von Jakob Hinrichs

laden wir Euch und Eure Freunde herzlich ein!

Donnerstag, 18. Oktober 2012. 20 Uhr

Büchergilde – Buchhandlung am Wittenbergplatz

Kleiststraße 19-21, 10787 Berlin

Wie entsteht aus einer klassischen Novelle eine Graphic Novel?

Der Illustrator Jakob Hinrichs präsentiert seine Ideen und die Umsetzung zur Gestaltung seines Buches und wird gern Fragen zu dem interessanten Thema beantworten.

Jakob Hinrichs ist Zeichner und Grafiker. Seine Illustrationen erscheinen in internationalen Publikationen und Zeitungen wie der New York Times. Er lebt und arbeitet in Berlin.

Traumnovelle: Der Arzt Fridolin wandert nach einem Ehestreit mit seiner Frau Albertine ziellos durch die nächtliche Stadt und erfährt zufällig von einem geheimen Maskenball. Dort angekommen, mahnt ihn schon bald eine mysteriöse Frau, schnell wieder zu verschwinden. Doch Fridolin ist entschlossen zu bleiben, fasziniert von dem wilden und bizarren Treiben auf dieser Orgie. In dieser Nacht gerät Fridolin in einen Strudel aus Sex, Gefahr, Fantasie und Illusion, der ihn – und seine Ehe – auf eine harte Probe stellt.

Arthur Schnitzlers Traumnovelle erschien 1926 und ist heute ein Klassiker der Literatur. Jakob Hinrichs adaptiert die Geschichte erstmals als Graphic Novel und erzählt sie in tiefgreifenden, fantastischen Bildern neu. Fridolin wird durch eine bildgewaltige Traumwelt getrieben, die mit schrägen und bizarren Charakteren bevölkert ist. Mit zahlreichen Querverweisen in die Kunstgeschichte ist die Lektüre der grafischen Traumnovelle ein besonderes visuelles Vergnügen.

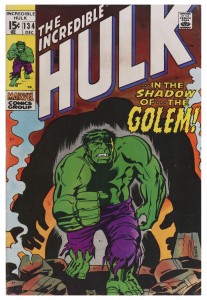

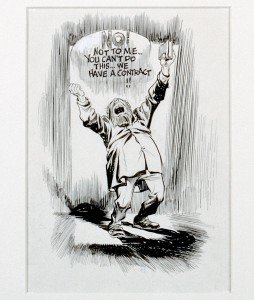

Seit dem 30. April läuft im Jüdischen Museum Berlin die Ausstellung “Helden, Freaks und Superrabbis”. Anhand von mehr als 400 Originalzeichnungen, Skizzen und Comic-Heften wird darin der Beitrag jüdischer Zeichner, Texter und Verleger zur Entwicklung des Comics gewürdigt. Zu den ausgestellten Künstlern zählen Vertreter des frühen Comic-Strips wie Milt Gross, Legenden wie Will Eisner (“The Spirit”, “A Contract With God”) und Jack Kirby (…viele, viele Marvel-Helden, u.a. Fantastic Four) sowie Zeichner wie Art Spiegelman (“Maus”) und Ben Katchor (“The Jew of New York”).

Kunsthistoriker und Comicexperte Jens Meinrenken war als wissenschaftlicher Berater an der Konzeption der Ausstellung beteiligt. Für den Katalog zur Ausstellung (120 S., 19,80 Euro) verfasste er einen Artikel zu amerikanischen Superhelden und ihren jüdischen Wurzeln.

Jens, die Ausstellung “Helden, Freaks und Superrabbis” lief ja bereits in Paris und Amsterdam, wurde aber für Berlin umkonzipiert und erweitert. Was genau wurde denn verändert?

Jens, die Ausstellung “Helden, Freaks und Superrabbis” lief ja bereits in Paris und Amsterdam, wurde aber für Berlin umkonzipiert und erweitert. Was genau wurde denn verändert?

Die Ausstellung wurde neben Paris und Amsterdam auch in Frankfurt und in Australien gezeigt. Soweit ich die verschiedenen Stationen überblicke, habe alle vier Orte eine eigene Form der Präsentation gefunden.

Die Unterschiede liegen in der Auswahl der Exponate, dem Verhältnis von Originalen und Reproduktionen und in der Ausstellungsarchitektur. Zum Beispiel sind in Berlin keine Zeichnungen von Hugo Pratt zu sehen, dafür wird versucht, die jüdischen Comicstrips von Samuel Zagat oder Zuni Maud stärker in die Entwicklungsgeschichte des amerikanischen Zeitungscomics einzubinden, beginnend mit Yellow Kid und der dortigen Darstellung des Immigranten-Milieus.

Welche Rolle hast Du bei der Umgestaltung gespielt?

Ich hatte die Rolle eines wissenschaftlichen Beraters zusammen mit Jens Balzer und Katja Lüthge. Jeder von uns hat verschiedene Ausstellungsbereiche zugewiesen bekommen, die wir dann auf der Grundlage der früheren Ausstellungen in Paris und Frankfurt konzeptuell überarbeitet haben. Die weiteren kuratorischen Aufgaben und die Entscheidung, welche Exponate tatsächlich gezeigt werden können, lagen allein in den Händen des Jüdischen Museums von Berlin. Wobei ich betonen möchte, dass ich die Zusammenarbeit als sehr angenehm und konstruktiv empfunden habe.

Was war Dein persönlicher Zugang zu dem Thema? Hattest Du dich vorher schon einmal mit spezifisch ‘jüdischen’ Comics beschäftigt?

Ich kannte die Sachen von Joann Sfar durch die deutschen Ausgaben aus dem avant Verlag und hatte bereits ein paar Aufsätze und Bücher zu dem Thema gelesen. Außerdem bin ich ein großer Fan von James Sturm und Ben Katchor. Für die Ausstellung habe ich mich gründlich in das Thema eingearbeitet. Ein kleiner Teil der Recherche findet sich in meinem Katalogbeitrag “Eine jüdische Geschichte der Superhelden-Comics” wieder.

Ich kannte die Sachen von Joann Sfar durch die deutschen Ausgaben aus dem avant Verlag und hatte bereits ein paar Aufsätze und Bücher zu dem Thema gelesen. Außerdem bin ich ein großer Fan von James Sturm und Ben Katchor. Für die Ausstellung habe ich mich gründlich in das Thema eingearbeitet. Ein kleiner Teil der Recherche findet sich in meinem Katalogbeitrag “Eine jüdische Geschichte der Superhelden-Comics” wieder.

Gibt es einen Teil der Ausstellung, der Dir besonders am Herzen liegt?

Nein. Die Ausstellung sollte als Ganzes wahrgenommen werden – mit ihren Brüchen, Wiederholungen, Details und auch Ungenauigkeiten. Nur so begreift man die Komplexität des Themas und bekommt ein Gefühl für die Fähigkeit des Comics, soziale, politische oder religiöse Inhalte optisch und sprachlich auf den Punkt zu bringen.

Was für Kontinuitäten gibt es überhaupt in einem Themenbereich der von frühen Zeitungsstrips bis zu modernden Graphic Novels reicht?

Kontinuitäten entstehen aus der Rückschau und Reflexion. Ein gutes Beispiel hierfür sind die ausgestellten Zeitungsseiten von Art Spiegelmans “Im Schatten keiner Türme”. Dort präsentiert sich Spiegelman als tanzende Wonder Woman und zitiert darüber hinaus viele Figuren des frühen amerikanischen Comics. Diese Form der Travestie hat ihre eigentlichen Wurzeln in der politischen Karikatur und Satire des 19. Jahrhunderts.

Kontinuitäten entstehen aus der Rückschau und Reflexion. Ein gutes Beispiel hierfür sind die ausgestellten Zeitungsseiten von Art Spiegelmans “Im Schatten keiner Türme”. Dort präsentiert sich Spiegelman als tanzende Wonder Woman und zitiert darüber hinaus viele Figuren des frühen amerikanischen Comics. Diese Form der Travestie hat ihre eigentlichen Wurzeln in der politischen Karikatur und Satire des 19. Jahrhunderts.

Ein anderes Beispiel sind die Zeichnungen von Will Eisner zu Beginn der Ausstellung, auf denen er in Form eines Künstler-Porträts über die Rolle des Comiczeichners sinniert.

Beim Lesen der Infotexte ist mir aufgefallen, dass die meisten der Künstler die in der Ausstellung behandelt werden aus den USA stammen oder zumindest dort gewirkt haben. Was für eine Rolle spielen jüdische Künstler für die europäische Comic-Szene?

Diese Frage wird in der Ausstellung nur angeschnitten. Dennoch sollte man nicht vergessen, dass viele der gezeigten Comiczeichner ihre familiären Wurzeln in Europa haben, deren Vorfahren nach Amerika eingewandert sind. Sicherlich werden einige Kenner der Materie René Goscinny in der Ausstellung vermissen, aber ich denke, dass mit Joann Sfar einer der momentan produktivsten jüdischen Comic-Künstler aus Frankreich vertreten ist.

Unter “Helden” und “Freaks” kann ich mir comictechisch noch etwas vorstellen, aber worauf beziehen sich die “Superrabbis” im Titel der Ausstellung?

Das ist ein Rätsel, dass der Besucher der Ausstellung für sich selbst lösen muss…

Danke, dass Du Dir die Zeit genommen hast!

“Helden, Freaks und Superrabbis”

30. April bis 8. August 2010

Jüdisches Museum Berlin, Altbau, 1. Obergeschoss

Montag: 10-22 Uhr, Dienstag-Sonntag: 10-20 Uhr

Eintritt: 4 Euro, ermäßigt 2 Euro

Katalog (120 S.) : 19,80 Euro

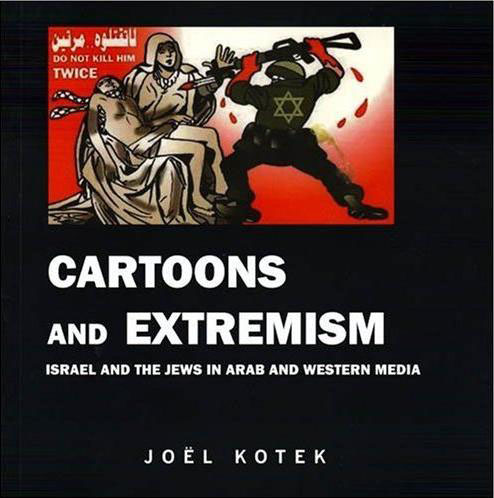

]]> Joël Kotek’s book is based on the observation that there has been a relatively recent (~ 2000) change of quality and amount of cartoons on Israel in Arab media.

Joël Kotek’s book is based on the observation that there has been a relatively recent (~ 2000) change of quality and amount of cartoons on Israel in Arab media.

These cartoons are – as one would guess – aggressively anti-Israel. Moreover, they are blatantly racist, often using images based on century-old anti-Semitic myths, termed “antisemyths” by the author. Since we are living in visual times, these cartoons can be dangerously effective in forming public opinion. The book’s intention is to “deprive [these depictions] of all legitimacy” by exposing them as what they truly are: myths without any foundation in reality.

The first chapter of “Cartoons and Extremism” looks at anti-Semitic myths like infanticide, host desecration and blood libels and traces them back to the 12th and 13th century. Chapter Two deals with the particularities of cartoons in the Muslim world and tells about changes in the depiction of Israel after 1967. The main part of the book, chapter 3, shows recent cartoons using the ancient myths and imagery that hardly differs from anti-Semitic cartoons in Nazi newspaper “Der Stürmer”. The last two chapter then deal with similar imagery in both mainstream European newspapers and leftist anti-globalization platforms and show how Israel is being used as a scapegoat and metaphor for modernity.

The book offers several explanations for the abundance of anti-Semitic imagery. The most prominent one aims at the structural conditions of the Arab media.

Authoritarian structures, says Kotek, prevent many Arab cartoonists from criticizing their own country’s political parties and leaders. Instead, they cut out on the social criticism and humor and deliver heavy, serious and moralizing pieces about an acceptable enemy: Israel and the Jews. These are printed in the majority of the major dailies in the Arab world. Therefore, in the epilogue Kotek sets out to denounce that editorial practice and to “alert the cartoonists of the Arab-Muslim region to a certain sense of responsibility”. In order to do so, he includes twelve theses by the father of peace research, Johan Galtung, pointing out common dangers in reporting on conflict. Some of which, I had the impression don’t really apply to cartooning.

“Cartoons and Extremism” is an interesting book to read, and I fully support its project to sensitize people for anti-Semitic imagery and scapegoating of Israel. It has, however, a couple of flaws that are at times irritating.

First and foremost, its arguments are somewhat weakly supported. Using lengthy quotes from other authors Kotek claims that antisemyths are a symptom of crisis and that anti-Zionism has ” become a means of drowning a feeling of vague guilt on the part of the West”. But he does little to prove this. I understand that the evolution of stereotypical of images in a given culture is a continuous process but since Mr. Kotek claims that there are some crucial dates that marked a change I was sort of waiting for an explanation on how these events changed cartooning. At times, the author’s way of depicting Israel, was leaving out important aspects of the Middle East conflict. I am aware of the danger of ending up saying “Well, it’s their own fault too” when talking about hateful stereotypes. Still, I was a bit annoyed when Mr. Kotek claimed that the scapegoat Israel was really “a defenceless animal”.

The books greatest strength as well as its second big flaw is its use of images.

There are plenty of them, and their number effectively communicates the fact that we are dealing with widely shared stereotypes and not with single cases of tasteless cartoons. On the other hand, I think that Kotek has been overdoing it. There is, for example, simply no point in spending 15 pages in order to show that Brazilian cartoonist Carlos Latuff (a toonpool.com member, by the way) is an anti-Semite. Several pictures are obviously jpegs in awful resolution, some even appear twice in the book. Personally, I could have done without the graphic photos of dead babies, too. The problem with the overabundance of images also ties in with the lack of argument. Some of them have no connection whatsoever with the written text – there’s a whole chapter on the “Strange Case of Greece” that manages to avoid telling what’s so strange about Greece.

In retrospect the book turned out abit disappointing, mostly due to its argumentative weaknesses. Still, I think raising awareness in artists and readers is a very important thing to do and that is something “Cartoons and Extremism” actually can do.

Joël Kotek. Cartoons and Extremism: Israel and the Jews in Arab and Western Media. Edgware, Middlesex: Vallentine Mitchell (2009).

Mr. Kotek, how come so many cartoonists, including both Arabic artists and Western anti-Globalization folks, are insensitive towards connections between their works and what you call “Antisemyths”?

Strangely enough they do not seems to understand ‘our’ point of view… They consider their work as strictly anti-Israeli and/or anti-zionist. How to explain this ? 1) complete ignorance: actually, they haven’t read my book) 2) hypocritical attitude (they know they produce harsh propaganda but refuse to admit it) 3) worst… they don’t understand our concern because they really share the Stürmer like demonic antisemitism. Personally, this is what I believe. I have no doubt about the fact that radical anti-Semitism is now growing in the Moslem world. My collection of Arab caricatures demonstrates this. The collective image of the Jews created by Arab cartoons lays the groundwork for a possibility of genocide. One can argue about whether these genocidal ideas are conscious or subconscious. My view is that they are still at the subconscious stage.

Strangely enough they do not seems to understand ‘our’ point of view… They consider their work as strictly anti-Israeli and/or anti-zionist. How to explain this ? 1) complete ignorance: actually, they haven’t read my book) 2) hypocritical attitude (they know they produce harsh propaganda but refuse to admit it) 3) worst… they don’t understand our concern because they really share the Stürmer like demonic antisemitism. Personally, this is what I believe. I have no doubt about the fact that radical anti-Semitism is now growing in the Moslem world. My collection of Arab caricatures demonstrates this. The collective image of the Jews created by Arab cartoons lays the groundwork for a possibility of genocide. One can argue about whether these genocidal ideas are conscious or subconscious. My view is that they are still at the subconscious stage.

What, in your opinion, is the connection between anti-Semitism and the common claim of cartoonists that they are merely “anti-Zionists”?

One cannot confuse between “anti-Semitism” and “anti-Zionism”. The argument and thus the graphic code are radically different. Even if I do not share this opinion, “anti-Zionism”, if not radical, is a legitimate opinion. You can be opposed to the idea of a Jewish state – even if it looks strange to me that any people can have a homeland (Kosovars, Palestinians, Kurds, etc.) but not the Jews.

The trouble is that what they believe are anti-Zionist cartoons are outright copies or plagiarisations of images from the Nazi press, foremost “Der Stürmer”. Paradox ally, it is at the very time when, after centuries of obscurantism, Europe discovered the virtue of tolerance, that the Arab-Muslim world united for blatantly expedient reasons to appropriate the stereotype that were hitherto unknown there.

I had the feeling that you were pretty vague about why and when exactly the number of anti-Semitic cartoons increased so greatly. Could you elaborate on that change?

The change came slowly after the 1967 war. Before 1967, the Israeli was just a “dhimmi” that could be very easily exterminated. They were then presented as little devil – the real evil and/or master being the American imperialism. After the 1967 defeat, everything changed since the dhimmi refuse to be exterminated. How could 300,000 million Arabs, one billion Muslims not be able to defeat a country as big as… Corsica ? Logically, the arrived to an phantasmal, but useful, explanation: the Jew as the personification of evil, the real master of the world.

Do you think an appeal towards artists’ and editor’s responsibilities like yours can be effective, when propaganda-style cartoons are a fixed feature of both Arabic newspapers and anti-Globalization websites? Do you know of any voices from within those circles demanding a more differentiated approach and a halt on anti-Semitic imagery?

As far as I know this happen only in Germany. Almost all national indymedia sites publish Carlos Lattuff’s anti-Semitic cartoons. The only one that had the courage to ban them was the German indymedia website.

I suppose one should organize conferences explaining the difference between a political and a racist caricature. What is a (political) caricature ? A criticism and/or an exaggeration of a reality. What is an anti-Semitic cartoon ? A pure invention ! The Israelis do not kill Palestinian children for ritual purposes ! Israelis and Jews are not ugly or evil by nature !

The idea would be to persuade the cartoonists and their bosses that there is a limit not to trespass : racism. In brief, to persuade them to adopt a code of good conduct. Actually this is, more a less, what the French cartoonist Plantu (Le Monde) is trying to organize under the auspices of the UN.

What would you say is the right way to deal with cartoons using anti-Semitic imagery on an international platform for cartoons like toonpool.com?

They should be banned. The limit of the freedom of expression is racism… As their Nazi counterparts, those cartoons are genocidal. They are “ruse de guerre”, “ruse de massacre”, to use the expression of Anthony Julius. Anti-Semitism (and/or racism) is not a opinion but a crime.

Thanks for your time!

]]> Kittihawk, you started drawing cartoons only in 2005 and now you got your first anthology published. The book is called “Lebenslanges Lernen” (Lifelong Learning) - Did you learn anything in these four years of doing cartoons?

Kittihawk, you started drawing cartoons only in 2005 and now you got your first anthology published. The book is called “Lebenslanges Lernen” (Lifelong Learning) - Did you learn anything in these four years of doing cartoons?

Yes, definitely. I always notice this when looking at my first cartoons: sometimes I don’t even think they’re funny anymore. Over time, you discover how you have to tell a story to make it funny. I’m better at that now, but I’m still learning new stuff. I am really interested in the different ways of telling a story.

I originally wanted to ask you about why most of your works are black and white, since most of your stuff on toonpool.com is. Then I noticed that there are lots of colored cartoons in your book.

Well, actually I think I really like black and white cartoons better. They have a kind of beautiful sternness to them. I only started using color a year ago, partly, because everyone does it. In a lot of cases, I don’t think that it’s necessary to use color and I really don’t like cartoons that look as if they have been colorized. Who knows, maybe colored cartoons will be out of fashion again in a couple of years.

Most jokes in your cartoons would work without an elaborate setting, but I noticed that you sometimes draw really detailed backgrounds. For example, I really liked all the small background items in the revised “phone-sex Nazi” cartoon. In what situations do you decide on doing these backgrounds?

Sometimes you need to place the action of the cartoon in a distinct setting to make the joke work. In other cases this is not crucial, but I still like to situate the cartoon somewhere. Some artist leave out settings altogether, but this also means a lack of ambience that readers can recognize and relate to. I really like it when you get the sensation of being in another place when looking a cartoon. That’s also something I really appreciate about other artists.

Do you try out different backgrounds for a cartoon?

Yes: often I will think of a joke and draw a background. Then I’ll notice that there is too much stuff in the background and have to remove it. Since I only work digitally, I can try out different things.

I noticed that people writing about you will often point out how you’re a woman doing a job that’s dominated by men – this is repeated in your press kit and even in the introduction to your book. What do you think about this?

I asked them not to emphasize this, but everybody does it. This happens with other female artists as well, it’s a kind of a cliché. It’s the same with reports about Angela Merkel: They often put an emphasis on her being woman working in a field that’s usually male. Maybe it’s natural that this is the first thing that people notice, but it’s sad when they don’t go on from there. It’s important to me not to me labeled as “woman cartoonist”, male artists don’t draw “men cartoons” either. We all interact with both men and women. Making up a “women cartoons” category is stupid.

Thanks for your time!

For those of you living in Berlin: An exhibition of Kittihawk’s cartoons will open on Friday, September 25 2009 at Cartoonfabrik Berlin (Krossener Straße 23, Friedrichshain). You are all invited to celebrate the opening & Kittihawk’s new book “Lebenslanges Lernen”. Doors open at 8 PM.

If you can’t make it or don’t live in Berlin or Germany, you should consider buying the book or try to get a free copy:

Win a signed copy of Kittihawk’s book “Lebenslanges Lernen” – just send an e-mail to [email protected] & put “Kittihawk” in the subject field. (any recourse to courts of law is excluded).

Paul Hellmich

]]>Mit „Voll dit Leben!“ tritt der Berliner Cartoonist Sam in die Fußstapfen des berühmten Heinrich Zille. Jetzt ist das Buch erhältlich bei toonpool.com für 15 Euro.

Das Berliner „Milljöh“ ist untrennbar mit dem Namen Zille verbunden. Der berühmte „Pinsel-Heinich“ prägte wie kein anderer das Bild der preußischen Industriemetropole – ein Moloch aus Mietskasernen und Maschinenhallen, der den Menschen kaum Luft zum Atmen ließ. „Wenn ick will, kann ick Blut in den Schnee spucken… “, lautet ein bekannter Satz aus dem Mund eines schwindsüchtigen Zille-Kindes. Mit bitter-ironischem Witz hat der Berliner Grafiker und Karikaturist das Leben in den Hinterhöfen, Hurenhäusern und Arbeiterkaschemmen zu einer sozialkritischen Proletenidylle veredelt und dem Berliner Dialekt bis auf den heutigen Tag internationalen Kultstatus verliehen.

Inzwischen sind die Fabriken modernen Innovationszentren gewichen. Aus den Eckkneipen wurden Coffee-Shops. Und aus den Mietshäusern durchsanierte Mittelstandsquartiere für den urbanen Akademikernachwuchs. Ist Zille damit endgültig ein Fall fürs Museum?

Nicht unbedingt: Mit Sam ist ein neuer Zeichner in die Fußstapfen des alten Meisters getreten und findet abseits der ausgetrampelten Szenepfade und Sightseeing-Touren noch genügend Stoff für seine Milieu-Studien. Es gibt sie noch, die „Ickes“ und „Kiekste was“, nur dass man sie nicht in der Ständigen Vertretung, im Borchardt oder in den zahllosen Strand-Cafés an der Spree trifft. Eher schon an der Wurst-Bude, wo eine Berliner Type das „Siebenjänge-Menü“ bestellt: „Eene Bratwurscht und ’n Sixpack Bier“. Sam, mit bürgerlichem Namen André Paff, holt sich seine Inspirationen aus Kneipen wie Puschel in der Potsdamer Straße oder dem Torpedokäfer im Prenzlauer Berg. Orten, an denen sich der selige Mief der Eckkneipe mit den bierschweren Ergüssen standorttreuer Tresen-Philosophen mischt.

Die Hölle, das ist nicht mehr ein Leben zwischen Kohlenschleppen und Kartoffelsuppe. Die Hölle, das sind die fortwährenden Kleinkriege mit aktuellen und verflossenen Lebenspartnern, die Widrigkeiten einer Hartz-IV-Existenz und die ewige Frage nach dem letzten Bier. Da sagt der Wirt zu Gast: „Du hast noch zwölf Bier vom letzten Mal uff’n Deck’l stehn.“ Sagt der Gast: „Kannste wegkippen, trinkt ‚eh keena mehr.“ Oder ein nackter Mann steht in der Wohnung und die Frau in der Tür sagt: „So meinte ick dit nich: Du bist ausjezogen, wenn ick nach Hause komm!“

Auch der bayerische Tourist in der Lodenjoppe mit Hirschhornknöpfen bekommt sein Fett weg, etwa wenn er fragt: „Wie komme ich denn in den Zoo?“ – und die Antwort lautet: „Als wat denn?“ Unverkennbar, hier hat der berühmte Eckensteher Nante als Vorbild gedient. Wie überhaupt der berüchtigte Berliner Humor mit seinem Charme wie aufgekochtes Spülwasser bei Sam gut aufgehoben ist.

Inzwischen sind Sams Alttagsbetrachtungen fester Bestandteil in den Berliner Medien. Im „Berliner Kurier“ hat er täglich einen Cartoon und in der U-Bahn kann man seine Zeichnungen auf dem Monitor bewundern. Jetzt hat er ein Buch herausgebracht. In „Voll dit Leben!“ finden sich 128 seiner besten Zeichnungen – ein Sammelsurium aberwitziger Proleten-Poesie. Wie der der Trinker, der vor Kumpels noch mal sein Leben Revue passieren lässt:: „Also wenn ick noch mal uff de Welt komm, denn wäre ick jern so wie ick“?“ Dem ist nichts hinzuzufügen.

Karl Hermann

(toonpool.com)

Voll dit Leben! Sam, 128 Seiten, 15 Euro

Hier geht’s zum Shop

Das Buch „Voll dit Leben!“ ist der Auftakt einer Reihe von Cartoon-Büchern aus dem toonpool.com-Verlag. Cartoonisten, die an einer Buchveröffentlichung interessiert sind, können sich gern bei toonpool.com melden.