Some time ago, I mentioned several collections on fine arts found on toonpool.com. Inspired by the amazing art spoofs by Costa Rican member Francisco Munguia, I decided to take a closer look at humorous versions of famous paintings.

Modernity and Spoofs

While I am not an art historian, I think it is safe to assume that parodies of visual art gained a great deal of importance in the 20th century. For a spoof to be effective, after all, people must be familiar with the original piece of art. Painted copies as well as engravings of works of art may have been available before. Photographic reproduction, however, vastly increased our repertoire of shared images and thus the number of people who would “get” a parody. As a result of this development and of the continuing democratization of publishing processes, the number of parodies itself increased.

Types of Spoofs

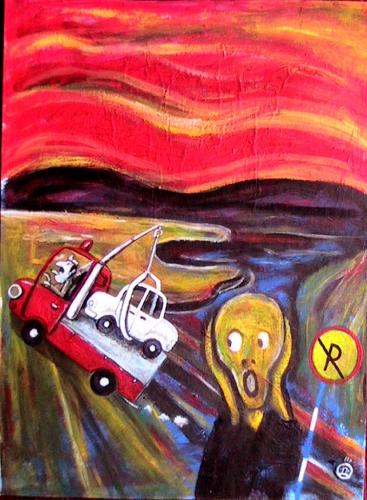

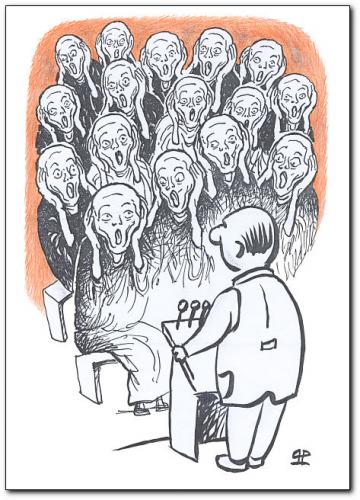

The most frequently spoofed painting on toonpool.com is Edvard Munch’s “Scream”. This is likely not only a result of the original’s fame but also of its cartoony-ness. The Scream Guy is, after all, easy to draw. The spoofs can roughly be divided into three categories. In the first category, the artist changes the content of the original image (e.g. here, here & here). In many cases this is restricted to only a few elements of the picture, but at times the whole painting is being reinterpreted (e.g. here & here). The second category consists in artists putting one element into different situations outside the original setting (e.g. here, here & here).

Spoofs of the third variant, finally depict the iconic image as a piece of art inside the cartoon narrative. Sometimes it is contrasted with other famous pieces of art (e.g. here & here).While “type one” is probably more frequently used than the other two, there is always some variation depending on whether the original image is suited for a particular type of parody. Take Michelangelo’s “Creation of Adam” – another favorite when it comes to parodies There are much less “type two” spoofs because it is not as easy to single out an element like Munch’s Scream Guy (there are some examples, though: here & here). There are a few “type threes”, too (here & here), but the majority is clearly “type one” (here, here & here).

Why We Spoof

The formal typology above is very likely incomplete and may have other flaws, too. It illustrates, however, the basic strategy of parody: artists introduce a new narrative, while the original narrative of the work remains in recognizable in the paintings’ visual elements.

Apart from the “joy of recognition”, I would argue, some of the pleasure we derive from looking at an art parody, stems from a playful questioning of the original piece’s authority. Sometimes the purpose of this attack is merely a gag (as in this version of Rembrandt’s “Anatomy Lesson”), sometimes it also includes a comment on our society, politics or even humanity as such (as in this manipulation of Shilder’s portrait of Alexander III. or this “Venus of Willendorf”).

Parodies may function as a means to satirize a concept symbolized by the original painting – for example creationism in the “Creation of Adam”. There are hardly any cases, though, in which the aura-laden original itself becomes the object of satire. Perhaps you could count the “Picasso face” gag (1,2,3), but on a closer look these are generalizations about those wacky Picasso portraits rather than true parodies of individual works.

In conclusion, I want to argue that, although parodies may somewhat question the original’s authority, they ultimately cement its status. Not only do they popularize its visuals, they also add their own weight to their subject’s assumed significance. If people bother to do a parody of a painting, goes the implicit argument, it must be important. Therefore spoofs are a potential force in the creation of cultural order. But most of all they are entertaining. Or inspiring. Or boring. It really depends.

Appendix

Art parodies are not restricted to the field of cartoons, at times they also show up in “serious” art. For example a spoof of Leonardo Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa was on display in an 1883 exhibition in Paris. Édouard Manet’s “Déjeuner sur l’Herbe” can, to some degree itself be considered a spoof. Originally considered offensive by many people, the 1862 painting is in parts a profanization of the mythical content of Raphael’s “Judgement of Paris” (look at that group of people in the lower right corner).

I want to close this article by pointing out the numerous examples for cartoon parodies of other cartoons. They, too, are often based on ridiculing the original version. Since most cartoon characters aren’t really put on a pedestal in the first place, the spoofs often have to be very rude to achieve their goal. I would argue that the internet’s overabundance of pornographic and violent images of famous cartoon characters partly results from this. The Tijuana Bibles of the 1920s to 60s are predecessors of these images. Luckily there are ways of creating parodies of cartoon characters that are more affectionate and original. You might want to check out the Covered Blog‘s re-imaginations of comic books (although you have to imagine the re-imagined comics – there’s only covers) and Dan Walsh’s amazing “Garfield Minus Garfield”. The End.